Physiological measurement. This approach takes measurements of human physiology (the structures and functions of the nervous system), to show how our biology affects our behaviour and experience. It can involve measuring the levels of hormones such as adrenalin in the body in order to study their effects (since these effects have been found to be quite context-dependent). Another example might involve measuring of the electrical resistance of the skin, indicating the amount of sweat generated (more technically, Galvanic Skin Response, or GSR) and looking for changes when people are telling the truth or lying. Here a relatively simple physiological measurement is being used as an indicator of underlying mental states.\nAn issue that can arise from use of physiological methods is the question of reductionism, in this context the extent to which complex human behaviour and experience can be explained entirely in biological terms. This is sometimes jokingly referred to as 'nothing-buttery', as in: “the experience of aggression is 'nothing but' the flow of adrenalin and the firing of particular neurons”. The resolution of debates like this require philosophical methods as well as physiological ones.

Psychophysics measures how people respond to basic physical sensations such as temperature and loudness, looking at things such as reaction times and sensory thresholds. A typical question for investigation would be, what is the minimum stimulus needed to perceive a particular sound?

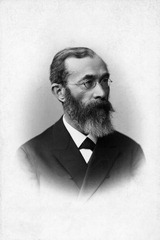

Introspection. Essentially, this method involves attempting to examine one's own psychological experiences (i.e. the contents and processes of the conscious mind) and report back what is found. This was one of the main methods of the early pioneers of psychology, such as William James, much of whose influential writings of psychology come from relatively informal and unstructured introspectionist reports of his own experiences. In a much more structured and formal way, Wilhelm Wundt established a psychological laboratory in Germany, where he tried to break down sensory experience into its component parts based on introspectionist data from a number of participants. In terms of the history of psychology, Wundt's failure to achieve inter-observer reliability with these types of data led to the rise of Behaviourism with researchers such as Watson rejecting mental data of all kinds as 'unscientific', and limiting psychology to the study of externally-observable behaviour. Since then, introspectionist data have more recently again found a place in psychology (though it's fair to say that introspection is still shunned by many psychological perspectives). In cognitive psychology, although the main focus is usually on experimental data, some cognitive psychologists have got people to 'talk through' their experiences when engaged in cognitive activities such as problem solving, with the resulting 'verbal protocols' seen as a useful complement to experimental data. Introspectionist reports of individual experience are an important part of humanistic and transpersonal psychology (e.g. in studying altered states of consciousness). These type of data are particularly important in transpersonal psychology, partly as a result of the way this perspective has been influenced by eastern philosophies/psychologies such as Buddhism, which have always used introspection as their primary method.