Genetic research. Human genetic research involves the study of inherited human characteristics. In the context of DSE212, the focus is particularly on possible insights into the origins of our psychological characteristics, including possible disorders (e.g. schizophrenia). The relationship between our genes and our individual psychology is not a simple one – there are complex interactions between different genes themselves, and between genes and the environment. The whole debate about the relative importance of biological and social explanations of human behaviour is a vigorous one within the social sciences generally. There are two main categories of genetic research – statistical and molecular – and these are described below in more detail: Statistical genetics. There are a number of different aspects of statistical genetics. Epidemiology involves the study of the distribution and origins of disease using statistical methods. Similar approaches can be used to estimate the genetic contribution to particular human disorders (or talents). In many cases, a particular genetic background doesn't provide 100% of the explanation for why a particular disorder occurs. Rather the genetic background gives rise to a stronger or weaker predisposition, which may be triggered by particular environmental or psychological factors. Statistical genetics may also be able to identify combinations of genetic and environmental risk factors that show there are particular subgroups of the general population who are at increased risk of a particular disorder.\nMolecular genetics. This method focuses on analysing the biochemistry underlying genes, and how this emerging knowledge can help increase understanding of human health and disease. Key aspects of the biochemistry of genes involve looking at how they are able to replicate and be transmitted, often in terms of the chemistry of the 'nucleic acids' DNA and RNA. The Human Genome Project is a major undertaking in a number of laboratories (particularly in the USA and Britain) to examine the location of every human gene and to examine the chemical structure of each gene, in order to find out the role the gene may play in affecting health and disease.

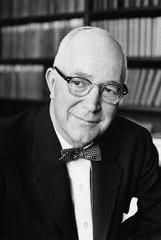

Anti-trait movement (1968). The anti-trait movement was launched by Mischel in 1968 in his book Personality and Assessment. According to Mischel, trait measures of personality showed little consistency across either settings or over time, and were of little predictive value, i.e. the person interacted with the situation (or environment) in which they found themselves. This is often referred to as the person-situation debate. To a degree, Mischel's thesis is similar in complaint to those that dogged attitude researchers at the same time - if traits or attitudes cannot predict behaviour, then what use are they? Defendants of trait theories argued that the studies chosen by Mischel to illustrate his point were particularly poor, and that better methodology would lead to better prediction of behaviour across time or situations. As with many debates in psychology, a great deal of effort was spent in trying to establish how much of people's behaviour can be predicted from knowing their traits and how much depends on the situation (i.e. person x situation interactions). Thus, if a personality measure of punctuality can predict 30% of the variance in a person's punctuality on a specific occasion, it inevitably follows that 70% of the variance is due to the situation. However, there are many difficulties in analysing what situation is and, in practice, it has generally been considered to be everything that is not the person (i.e. not a trait). As a result, there has been little advance in understanding what aspects of the situation or environment influence behaviour.