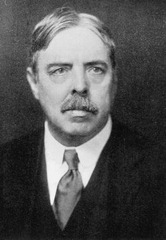

Behaviourism was a highly influential school of psychology founded by JB Watson in the early part of the twentieth century (though with earlier roots in the work of Thorndike and Pavlov). Its primary feature was a rejection of many methods used by psychologists up to that date, in particular the value of 'introspection': the idea that psychologists could gain useful insights by looking within their own minds. As explored by Wilhelm Wundt and his followers, introspection led to serious problems of reliability and validity, with disagreements among observers who were reporting responses to the same stimulus. Watson's solution to this methodological impasse was radical – he proposed that if psychology was to be properly 'scientific' (in the manner of the natural sciences, such as physics, chemistry and biology) then it must reject the study of mental events entirely, and confine itself to the study of externally observable behaviour (hence the name behaviourism). The basic idea was that behaviour can be understood entirely without reference to the concept of mind or consciousness, simply by looking at connections between the stimuli applied to a particular organism, and the resulting responses. Behaviourism's insistence on rigorous scientific methodology is still influential in many fields of psychology today, even though its original denial of mental representations has been largely discarded.\nAnother feature of Watson's approach was to look for parallels between humans and other animals in terms of common features involved in learning processes. In particular, the laboratory rat occupied pride of place in many a psychological laboratory, providing insight into issues such as conditioning and reinforcement. Another key aspect of Watson's critique was on the previous importance given by many psychologists to 'innate' factors (i.e. those present at birth, governing behaviour by instinct rather than through learning of some kind). While Watson did not deny the existence of such aspects (suggesting that learning builds on innate factors), he argued that innate factors had been overemphasized, and that psychologists had underestimated the role of environmental factors. If true, this clearly has major implications well beyond psychology – for example, for debates about selection for secondary schooling. It is interesting even today to look at the debates between politicians of different hue, depending on whether they see crime as primarily caused by environmental factors, or by the innate criminality of the individual. Depending on which one is thought to be the more correct, very different social policy responses would be suggested.\nBehaviourism takes a deterministic stance, largely (or entirely) denying possibilities of human agency. Humans aren't seen as having the capacity for exerting conscious choice, but either react to stimuli or emit behaviour according to how they have been conditioned. A simple early study of classical conditioning involved Pavlov's famous work with dogs, who were trained to salivate on hearing a bell, sounded at the times they were fed. Eventually they would salivate at the sound of the bell alone, even without the presence of actual food. Humans may have much more complex 'contingencies of reinforcement' (and other types of conditioning, such as operant conditioning, where reinforcement is only given if the organism produces a specific response), but were seen by behaviourists as essentially similar in that they could be conditioned to react to stimuli (or emit behaviour). \nBehaviourism can be defined in two primary ways: • The weak definition, or methodological behaviourism, simply says the best strategy pragmatically for psychology as a discipline is to confine study to observable events: external behaviours. This approach doesn't necessarily deny that mental events are real, just that they can't be successfully studied scientifically. • The strong definition, or radical behaviourism, goes further, in actually rejecting the very concept of mental events. For example, Watson argued that thinking is just silent speech, i.e. not a private, internal process, but a behaviour that could be observed in principle (if the observer could pick up the very soft speech the thinker says to him or her self). Consciousness is seen as either just a brain by-product, with no causal effect on behaviour, or even completely non-existent. This approach to behaviourism originated with Watson, and was subsequently adopted and modified by Skinner. Some of the consequences of a strict, radical behaviourist viewpoint (such as the lack of conscious choice) have been explored by Skinner in his novel Walden Two. Although such a viewpoint has a limited following among contemporary psychologists, the pragmatic emphasis of methodological behaviourism still carries quite a strong resonance for many experimental psychologists, with externally-observable actions seen as central to psychological research, even if interpreted within a quite different theoretical context to that of behaviourism.