Intelligence is a shorthand term covering a complex range of human capacities. There are no universally accepted definitions, but intelligence is generally taken to relate to factors such as the capacity to make sense of abstract ideas and to perceive patterns of complex relationships. There are many factors which relate to 'intelligence', such as capacity for insight into human relationships, verbal and numerical ability, non-verbal insights, 'motor intelligence' (such as ability to quickly master complex motor tasks like driving or tennis); 'emotional intelligence'; 'spiritual intelligence', and so on. A key assumption of many early workers in the field was that all such abilities factors simply reflected an underlying 'general intelligence'. Such a viewpoint would probably be seen as oversimplified these days. It is more likely that intelligence involves a constellation of partly interdependent factors, such as verbal and numerical ability, visuo-spatial ability, or visual pattern-recognition.

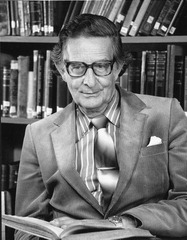

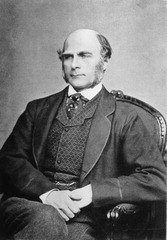

The nature-nurture debate (1955 – present day). Between the mid 1950s and the early 1980s one of the main debates that dominated psychology was nature-nurture. The crux of the nature-nurture debate was the degree to which human attributes, particularly intelligence and personality, were determined by either genetic factors (nature) or environmental factors (nurture). This nature-nurture debate was particularly fierce in the area of intelligence, following the publication, and subsequent criticism, of Sir Cyril Burt's results from his study of the intelligence quotients (IQ) of separated twins. Over many years Burt claimed to have studied 58 pairs of monozygotic (MZ – from the same ovum) twins (popularly referred to as 'identical'). This was a larger number than any other researcher had been able to obtain. For that reason, Burt's claims that the IQs of separated MZ twins were more alike than those of dizygotic (DZ – 'non-identical') twins reared together was very influential in supporting claims that intelligence is largely inherited. However, it was later alleged that Burt at worst fabricated his results, and at best behaved in a 'dishonest manner' because he did not find as many separated twins as he had claimed. The debunking of Burt's results even became the leading article on the front cover of an issue of the Sunday Times in 1976 and Burt was posthumously discredited by the British Psychological Society (BPS). The nature-nurture debate over intelligence generated a public debate between a leading hereditarian (someone who believes that intelligence is largely inherited) – Hans Eysenck – and the environmentalist who had first uncovered problems in Burt's reported statistics (Leon Kamin). This was published in 1981 in a book titled Intelligence: the battle for the mind. The debate has rumbled on since with publications such as The Bell Curve by Herrnstein and Murray (1994) and with various defences of Burt's conclusions and data. Few psychologists now argue for only one side of the nature-nurture debate. This is partly because most now accept that both genetic inheritance and environment play some part in all human psychological processes. The successful mapping of human genes in the Human Genome project has contributed new evidence to discussions of the heritability of psychological characteristics. However, the debate in psychology is now more one of the relative contributions of nature and nurture, and the specific mechanisms of interaction, than one of absolute dichotomies. Written by: Course Team

Genetic research. Human genetic research involves the study of inherited human characteristics. In the context of DSE212, the focus is particularly on possible insights into the origins of our psychological characteristics, including possible disorders (e.g. schizophrenia). The relationship between our genes and our individual psychology is not a simple one – there are complex interactions between different genes themselves, and between genes and the environment. The whole debate about the relative importance of biological and social explanations of human behaviour is a vigorous one within the social sciences generally. There are two main categories of genetic research – statistical and molecular – and these are described below in more detail: Statistical genetics. There are a number of different aspects of statistical genetics. Epidemiology involves the study of the distribution and origins of disease using statistical methods. Similar approaches can be used to estimate the genetic contribution to particular human disorders (or talents). In many cases, a particular genetic background doesn't provide 100% of the explanation for why a particular disorder occurs. Rather the genetic background gives rise to a stronger or weaker predisposition, which may be triggered by particular environmental or psychological factors. Statistical genetics may also be able to identify combinations of genetic and environmental risk factors that show there are particular subgroups of the general population who are at increased risk of a particular disorder.\nMolecular genetics. This method focuses on analysing the biochemistry underlying genes, and how this emerging knowledge can help increase understanding of human health and disease. Key aspects of the biochemistry of genes involve looking at how they are able to replicate and be transmitted, often in terms of the chemistry of the 'nucleic acids' DNA and RNA. The Human Genome Project is a major undertaking in a number of laboratories (particularly in the USA and Britain) to examine the location of every human gene and to examine the chemical structure of each gene, in order to find out the role the gene may play in affecting health and disease.

Neuropsychological basis of the mind/consciousness. Neuropsychology examines how neurological processes in the brain affect both behaviour and the experience of consciousness. This involves studying the brain, for example by examining the structure of the brain and the corresponding neural activity within it. Another approach is to examine damaged brains, looking at the consequences of the damage for behaviour, perception and language. Many cognitive functions have specific centres in the brain, though some cannot be localised in this way, and attention has turned instead to the identification of networks of interacting brain areas.