Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Festinger, Goffman, Gibson, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Festinger, Goffman, Gibson, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baron-Cohen, Asch, Bilig, Belbin, Bruce, Buss, Ceci, Cohen, Cooper, Conway, Damasio, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Eysenck, Ekman, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Gibson, Galton, Goldberg, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Maslow, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Vygotsky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Festinger, Goffman, Gibson, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Festinger, Goffman, Gibson, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Festinger, Goffman, Gibson, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Fodor, Festinger, Goffman, Gibson, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

World War I (1914 - 1918). Psychology was first used widely in the First World War in 1917, when mass psychometric testing was carried out by the US Army. Psychologists also studied 'shell shock' or war neuroses (later recognised as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder or PTSD)\nIt could be argued that applied psychology was effectively born during World War I. For instance, studies of fatigue in munitions factories were the first major industrial psychology studies to be conducted. Psychologists also worked on specific programs, like for instance, the selection of hydrophone operators best suited for 'hearing submarines'. According to Hearnshaw (The Shaping of Modern Psychology, 1989), the work of psychologists during World War I “helped to establish the claims of applied psychology, and led to its continuation on a still small, but nevertheless significant, scale” (p. 200). Written by: Course Team

Humanistic. Psychologists such as Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers developed humanistic psychology in the late 1950's as a 'third force' in reaction to the then prevailing disciplines of behaviourism and psychoanalysis. Humanistic psychology shared the rejection by psychoanalysis of the behaviourist insistence on studying only those aspects of human psychology which were open to precise observation and measurement. Also like psychoanalysis, humanistic psychology wished to examine subtleties of what it feels like and means to be human which are difficult (if not impossible) to capture in experimental settings. However, unlike psychoanalysis, humanistic psychologists took a much more optimistic viewpoint on people's capacity to be consciously aware of themselves, and of their capacity for agency (i.e. to consciously initiate change in their lives). It also takes a holistic approach, attempting to study the 'whole person' – thoughts, feelings, and bodily awareness. Humanistic psychology has developed or influenced a wide range of methods for facilitating personal growth, such as: Bioenergetics, Rebirthing.; Rogerian counselling, Encounter groups, Gestalt therapy, Co-counselling, Personal Construct therapy, Neuro-Linguistic Programming, Rational-emotive therapy; Psychosynthesis and many others. Research methods used by humanistic psychologists typically take an 'inside' viewpoint (in contrast to the 'outside' viewpoint of many other perspectives in psychology), using qualitative methods to try to understand people's subjective experience. They also take an 'idiographic' approach, in that they typically try, as much as possible, to understand people in terms of each person's unique way of viewing themselves and their world. So instead of experiments or psychometric measures, humanistic psychologists might use methods such as depth interviews. There is a considerable focus on helping people achieve their full potential, or self-actualization, in Abraham Maslow's term ('becoming all one is capable of becoming'). This is a quite different aim for psychology than, say, an experimental focus on eliciting reliable, 'scientific' data about cause-effect relationships. The best way to understand why different perspectives in psychology have such different methodologies, and focus on such different subject areas, is to ask, quite simply, what their aim is. There have been many critiques of humanistic psychology. As mentioned above, it is criticised for its lack of experimental methodology. Another criticism is that although it does acknowledge the existence of social influences, it arguably underplays the extent to which these construct many aspects of human experience (and, indeed, the way humanistic psychology itself can be seen as a product of postwar US culture, in its individualism and optimistic focus). It does not attempt to provide, as psychoanalysis does, a comprehensive theory of why we are as we are. Although, like the psychoanalytic perspective, humanistic psychology has had limited influence within academic psychology (because of its non-experimental focus), it has had a great influence in counselling and the various 'human potential' therapies. I has also had influence on teaching, and with aspects of work (e.g. some methods used in managementtraining and the development of interpersonal skills). At its best humanistic psychology provides conceptual frameworks and methods for encouraging personal growth that many people have found extremely valuable in their everyday lives. Ultimately, not unlike psychoanalysis, it takes an essentially pragmatic viewpoint in seeing the value of humanistic ideas and methods in their practical efficacy in helping human beings to lead more fulfilled lives.

Identity. The basic concept of identity refers to an individual's sense of themselves as a particular person, which will usually include their perception of their own social role(s). Another term which is also used is the idea of the self. At the level of human experience, the idea of 'self' basically refers to a fundamental sense of continuity experienced by most human beings that a particular unique entity - themselves - persists throughout all the changes in body, mind, social role etc. that occur throughout life. However, despite this sense of continuity at a deep level, there are also shifts in identity/self-image that can occur at various stages of life (e.g. adolescence), often in response to changing social roles. If severe enough, these transition points can be called identity crises.

Views: TOPICS, Allport, Erikson, Freud Sigmund, Falschung, Festinger, Goffman, James, Neisser, Mead, Tajfel, Spears, Turner, Vygotsky, Wetherell

Experimental (incorporating: Multivariate experimental comparison, Quantitative data collection, Intervention, Quasi-experimental, Cross-sectional) Quantitative data collection Experiments tend to focus on quantitative data, i.e. information in the form of numbers of some kind. It is perfectly possible for qualitative data to be gathered as well, i.e. information in verbal form, though usually in experiments this is seen as of secondary importance compared with quantitative data. Quantitative data do have some disadvantages in that much of the 'richness' of human psychological processes is necessarily lost in reducing it to numerical form. However, there are also many advantages to these forms of data (which is why they have played such a large role in psychological research). Firstly, it can be easier to compare quantitative data from different researchers who are using the same measures, compared with qualitative research, where data can not be 'standardised' in the same manner. Once data are in quantitative form, all sorts of mathematical and statistical manipulations can be employed, giving rise to possibilities that simply don't occur with qualitative research (which does, of course, has its own strengths, as described in the 'methods' section describing these forms of data). For example, average (or mean) scores can be worked out (and perhaps used to compare different groups of people, or between experimental conditions). Statistical tests can be used to calculate whether differences between particular scores are likely to reflect a genuine psychological phenomenon (or are just due to random fluctuations in the data). Other statistical techniques can be used to see if different aspects of data are associated with each other (or 'correlated'). The power of quantitative data can be very easily seen with sciences such as physics, which has given human beings great understanding and control over our natural world. Many psychologists over the past century or so have aspired to placing psychology on the same kind of footing. Experimental Method\nExperiments have been the most commonly used psychological method over the last century of psychological research. It aims to discover if there are 'cause-effect relationships' between variables by changing one variable (the 'independent' variable), and measuring the results of this on another psychological factor (the 'dependent' variable). While doing this, the experimenter will attempt to control all other variables that may affect the results, so that whatever changes occur can be explained in terms of the effect of the independent variable. There is a clear distinction here from observational methods, in that this method is based on a deliberate intervention by the researcher. Experiments can be done in natural settings or in laboratories, though because of the need to control other factors (not easy to do 'in the field'), the majority of experimental research has been done in laboratory settings. ('Laboratory', for a psychologist, often just refers to a room with a computer.) There is something of a trade-off here for a psychologist – the more 'controlled' the setting is, the more certain the psychologist can be that the results are due only to changes in the independent variable and nothing else. However, the very measures taken to reach this careful control can result in an environment unlike 'everyday life'. There is then the question, 'will the results still apply outside the laboratory, in everyday life?' (which is, after all, the usual aim of psychological research). This has been a particularly strong issue for social psychology (e.g. when looking at how people in group come to make decisions), where the socio-cultural setting is clearly going to be a significant component. It is arguably less of a problem with cognitive psychology, where memory research, for example, has benefited from being able to isolate particular memory processes from their everyday contexts. \nWithin the general field of experimental research, there are a number of specialised methods, such as:\nMultivariate experimental comparison. Multivariate approaches are designed to assess the affects of multiple variables simultaneously, instead of just looking at a single variable. This is very important in dealing with complex psychological processes which often have more than one cause. Quasi-experimental, Experiments involve two or more experimental conditions. Ideally, researchers will have full control over who is allocated to the different conditions, e.g. by randomly allocating people to one or other condition. However, with quasi-experimental designs, this control is limited in some way. An example might be research into gender differences, – people are already either men or women, so obviously can't be randomly allocated to the different conditions. Another example might involve looking at people's psychological reactions to experiencing a rail crash (compared with a control group who weren't in the crash). Again, the participants aren't randomly allocated between the conditions. The possibility then arises that there is some other distinction between the groups apart from the chosen independent variable which is giving rise to any differences found in the results. In the second example above, perhaps train travellers in the rail crash are untypical in significant ways from the people in the control group (e.g. if it was a commuter train, there is likely to be an age bias, and possibly also class, gender etc.). One way to try and limit these effects is to use matching – the people in the control group may be chosen to match the people in the 'rail crash' group on age, class, gender and so on. The difficulty is that the researcher can never be certain to have matched all the variables that have an effect. However, for many phenomena (such as the examples above) this method may be the only way possible to study them experimentally. Cross-sectional Studies Cross-sectional research is the most commonly used survey research design. It can provide good descriptions of the characteristics of the groups on whom the research is done and the differences between them. With this method, groups of people are selected from different sections of society. For example, they can come from different age bands. The researchers then compare these different groups (at more or less the same moment in time), looking for developmental trends, or age-related changes. \nThis method is commonly used in developmental psychology, to provide data which can be used to examine developmental theories such as Piaget's theory of cognitive development, or Freud's theory of emotional and personality development. Researchers may also do cross-sectional studies with factors such as social class, gender, ethnicity or occupational group being the basis of the division. One potential disadvantage of cross-sectional studies is that researchers can't be sure two different groups are similar enough for direct comparison. This would mean that there may be other reasons they are different, apart from the one the researcher assumes accounts for the difference. The longitudinal method is designed to overcome this disadvantage.

Views: METHODS, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asch, Bartlett, Belbin, Bruce, Cattell, Ceci, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Conway, Csikszentmihalyi, Eysenck, Ekman, Ebbinghaus, Frith, Fodor, Festinger, Gibson, Galton, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Pinker, Tajfel, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Thorndike, Taylor, Vrij Aldert , Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten

Neuropsychology. Theories relating mental processes to particular parts of the body go back to the Ancient Greeks – e.g. philosophers such as Empedocles and Aristotle located the mind in the heart, whereas Hippocrates located it in the brain. Modern neuropsychology examines how neurological processes affect behaviour. Essentially, the study of relationships between brain and behaviour. This involves the study of brain function, for example by examining the structure of the brain and the corresponding neural activity within it. Another approach is to examine damaged brains, looking at the consequences of the damage for behaviour, perception, language etc.. Although correlation between a particular cognitive or behavioural deficit and damage to a specific brain region cannot be taken as conclusive evidence that this part of the brain is the 'source' of this cognitive function, it clearly demonstrates that this region plays some kind of an essential role in relation to this function. Examples of this in relation to language processing were discovered in early research performed by Broca and Wernicke, in the nineteenth century. However, it has sometimes proved remarkably difficult to localize certain mental processes, in particular memory, to specific regions of the brain. This has led to a shift of emphasis, from looking for particular locations (e.g. localisation of memory functions) towards examining brain processes involved in storage and retrieval of memories.\nIn addition to examining human brains, experiments upon animal brains are also carried out by neuropsychologists, in the hope of providing insight into human brain processes. For obvious ethical reasons, deliberate damage cannot be inflicted on human brains in order to study resulting psychological deficits from particular brain lesions, whereas current ethical/professional standards do allow this with animal studies (though not without strong disagreement from a number of quarters).\nOther methods involve electrical stimulation of human brains during surgery, performed under local anaesthetic, with the patient therefore conscious and able to report any resulting sensations (it should be noted that such research is only carried out as a by-product of necessary clinical intervention). The rate of blood flow to different regions can also shed light on neuropsychological questions, as can electrical recordings of brain activity. These techniques are 'non-invasive', such as magnetic resonance imaging.\n(see also NEUROPSYCHIATRY, under PSYCHIATRY)

Views: PERSPECTIVES, Allport, Baron-Cohen, Cohen, Conway, Damasio, Crick, Frith, Gathercole, Gregory, Luria, Morton, Milner, Penfield, Pavlov, Sperry, Triesman, Weiskrantz, Warrington

Personality structure and Personality development . The term 'personality' can have widely divergent meanings. It can be seen as the outcome of the factors that make a person different from others in their patterns of thought, values, beliefs, emotions, and social roles and relationships. But personality can also be seen as the 'something'- the underlying construct- that leads to people's consistency in the way they behave and what they feel, over time and across many situations. In this sense, personality may be essentially unique to each of us but it can also be seen as a profile of underlying dimensions (possibly with a biological bases) that are common to many people.\nPersonality is an important concept in clinical, psychoanalytical and psychiatric contexts, particularly in terms of diagnosing and treating people seen as having disorders of the personality (such as compulsive, psychopathic, or paranoid personality disorders).

World War II (1939-1945). The Second World War had two main effects on the development of psychology. Firstly, a diaspora of Jewish intellectuals from Europe arrived in Great Britain and the United States, and secondly, psychological research was funded, and used extensively during the war.\n\n1. The diaspora. The diaspora refers to the scattering of Jewish people around the world before, during and following the Second World War. This scattering of intellectuals had a pronounced effect, not because of the psychologists who fled, but also because of the many US or UK psychologists who came into contact with many new ideas for the first time. This included not only fellow psychologists, but also philosophers, linguists and novelists. As well as the Jewish diaspora, a large number of gentile intellectuals also left Germany and mainland Europe before and during the war, often for New York or London, where they interacted and greatly influenced the existing scholars. According to Peter Robinson, who edited a volume of essays dedicated to Henri Tajfel “…it is thanks to the émigrés of Henri's generation that the field gained a foothold in the academic world” (Robinson, 1996, p. xi). 2. Applications of psychology. Unlike the First World War, when the application of psychology began only towards the end, psychology was used almost immediately from the beginning of World War II. Also, unlike World War I, where most psychological input was in the selection of recruits or treatment of 'shell shock', during World War II psychologists contributed in a variety of different areas. For instance, psychologists worked on: • Personality psychometrics – Psychologists devised tests used for the selection of 'officer material' and in the main combatant forces. In the UK, the War Office Selection Boards were set up in 1942 for this purpose, and by 1945 some 100,000 applicants for officer rank had been psychometrically tested. Also, during the war factor analytic techniques first applied on a mass scale – for instance, H.J. Eysenck studied 700 patients at the Mill Hill Emergency Hospital during the war. This research was the basis for his subsequent theory of personality. • Psychiatric disabilities of war – For instance, work at the Tavistock Clinic on Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and Psychoanalytic theories. • Attitude research - large research programs on attitude change and persuasion were funded by the American Army during the war. Related research on leadership and group behaviour was also extensively funded during this period. • Interaction with equipment – World War II was unique in its reliance on human operation of new technology, in areas as diverse as air traffic control, radar or code breaking. This led to psychological research into topics such as vigilance, training, stress and decision making. During this time, some old concepts (e.g. attention) were investigated with new vigour, while new concepts (e.g. stress) were developed as explanatory concepts. • The rapid development of neuropsychology in the 1950s was very much based on studies of combat victim's head wounds and their subsequent psychological functioning. Written by: Course Team

Views: CONTEXTS, Allport, Asperger, Bartlett, Csikszentmihalyi, Erikson, Eysenck, Freud Anna, Festinger, Gibson, Heider, Lazarus, Kanner, Mayo, Lorenz, Maslow, Milgram, Tajfel

Experimental Social Psychology. A classic definition of experimental social psychology was given by Gordon Allport, as the perspective which 'attempts to understand and explain how the thought, feeling or behaviour of individuals are influenced by the actual, imagined or implied presence of others.'\nIn the same way that psychology overall can be seen as a fragmented discipline, there are at least two distinct approaches to social psychology. There is very limited mutual recognition between these two approaches, as their fundamental assumptions are so different. The key is how the relationship between the self and the social context is approached. Experimental social psychologists tend to come from the broad approach of Psychological Social Psychology (PSP), where social psychology is seen as a branch of general psychology, and comprises the study of how basic aspects of individual's psychological functioning are modified in a social context. Essentially, the social context is seen as an additional variable. This can be contrasted with Sociological Social Psychology, which sees the relationship between the social and the self as inextricably linked and mutually influencing each other (see SOCIAL CONSTRUCTIONISM and SOCIOLOGY). Experimental social psychology frames its questions so that that they can be studied using carefully controlled experimental methods. Like all experimental approaches, it is looking for looking for reliable information about cause-effect relationships. It is possible to do 'field experiments' in a natural setting, and important work of this kind has been done (e.g. on inter-group relations). However, in order to maintain careful control of variables the topics quite often have to be simplified and taken out of 'real life' into the psychologists' laboratory in order to obtain reliable data. Not only does this move into the laboratory necessarily reduce the complexity of what can be studied, but it also can produce different results from those gained in natural settings. Although this can be a problem even with research into cognitive topics like perception and memory, this is likely to be a particular challenge for social psychology, as the social context provided in a laboratory experiment is necessarily different in non-trivial ways from social contexts in the outside world. However, for the experimentalist, the increase in control that the laboratory can offer provides a good trade-off, as long as the potential errors in generalizing the results to the 'real world' are kept in mind. \n\nWhile cognitive psychologists began with perception and moved towards inclusion of the social world, social psychologists began in the social environment, with perception of 'social objects' such as people, events, and social issues. The first social psychologists used people's attitudes - made up of their beliefs and feelings - about other people and social issues so as to understand social behaviour. What we believe or know and how we think (our cognitions) have also always been at the centre of theories about how we perceive people – hence much experimental social psychology is concerned with social cognition. The roots of social cognition can be traced back to the contributions of Fritz Heider, an Austrian born psychologist who moved to the USA in 1930, about the same time as many European academics of his generation who managed to avoid Nazi persecution in the Second World War.\nSocial psychologists like Fritz Heider argued that in order to understand social behaviour we must pay attention to how people perceive and struggle to understand their social world. A crucial notion is the idea that people operate like 'intuitive scientists', trying to make sense of their world in terms of regularity and predictability. This will involve building models of cause and effect, so as to control what happens in their lives. Heider applied these ideas to how we perceive other people and their actions, and our attributions of cause and effect, leading to the topic of 'attribution theory'. \nOther social psychologists in this tradition have built upon the research of pioneers such as Heider to apply experimental approaches to the study of topics like: intergroup relations group performance social influence in small groups aggression conflict and cooperation social relationships interpersonal communication social cognition.

Views: PERSPECTIVES, Allport, Baron-Cohen, Asch, Cooper, Ekman, Falschung, Festinger, Gregory, Heider, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Loftus, Milgram, Tajfel, Spears, Turner, Tversky, Zimbardo

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Festinger, Goffman, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

Views: Ainsworth, Allport, Baddeley, Baron-Cohen, Asperger, Asch, Bartlett, Binet, Bilig, Belbin, Bowlby, Bruce, Buss, Cattell, Ceci, Byrne, Bruner, Bryant, Cohen, Cosmides, Cooper, Chomsky, Charcot, Conway, Damasio, Darwin, Costa, Dawkins, Csikszentmihalyi, Crick, Erikson, Eysenck, Ekman, Descartes, Ebbinghaus, Dennet, Frith, Freud Sigmund, Freud Anna, Falschung, Festinger, Goffman, Goodall, Galton, Goldberg, Gathercole, Gregory, Humphrey, James, Heider, Janet, Goodman, Kahneman, Lazarus, Jung, Kanner, Klein , Kelly, Mayo, McCrae, Luria, Loftus, Lorenz, Maslow, Neisser, Norman, Morton, Milgram, Milner, Mead, Potter, Plomin, Piaget, Pinker, Penfield, Pavlov, Tajfel, Sperry, Skinner, Saywitz, Spears, Rogers, Turner, Triesman, Tulving, Tooby, Thorndike, Taylor, Weiskrantz, Vrij Aldert , Watson, Warrington, Vygotsky, Tversky, Wundt, Zimbardo, Whiten, Wetherell

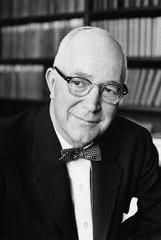

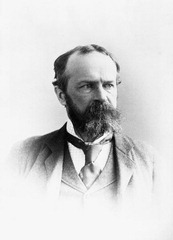

The self, he contended, is an identifiable organisation within each individual and accounts for the unity of personality, higher motives, and continuity of personal memories.

The self, he contended, is an identifiable organisation within each individual and accounts for the unity of personality, higher motives, and continuity of personal memories.

Tags: biography

His important introductory work on the theory of personality was Personality: A Psychological Interpretation (1937).

His important introductory work on the theory of personality was Personality: A Psychological Interpretation (1937).

Appointed a social science instructor at Harvard University in 1924, Allport became professor of psychology six years later and, in the last year of his life, professor of social ethics.

Appointed a social science instructor at Harvard University in 1924, Allport became professor of psychology six years later and, in the last year of his life, professor of social ethics.

Allport is best known for the theory that although adult motives develop from infantile drives, they become independent of them.

Allport is best known for the theory that although adult motives develop from infantile drives, they become independent of them.

He also made important contributions to the analysis of prejudice in The Nature of Prejudice (1954).

He also made important contributions to the analysis of prejudice in The Nature of Prejudice (1954).

Tags: contributions